Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

In April 2012, Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs Ahmet Davutoglu authored a paper that was to be the basis for Turkey’s Arab Spring doctrine — a “values-based foreign policy” for a region in flux. Davutoglu articulated an interventionist approach according to which Turkey would pursue greater regional integration and encourage representative democracy. He also repeated a central theme from his book, Strategic Depth, pledging that Turkey would work to avoid “new tensions and polarizations” in the region, particularly along sectarian and political lines.

Three years later, the positive vision of Davutoglu’s manifesto seems jarring, and nowhere more so than in neighboring Syria. Turkey has gone to incredible lengths to assist Syrian civilians in need, and it has cultivated ties with an array of political and military actors in the Syrian opposition. Yet Turkey has also invested heavily in rebel allies that both reject democracy and espouse extreme sectarianism. In particular, Turkey has developed a close relationship with Ahrar al-Sham, a Salafist rebel movement that espouses a Syrian focus, but also has roots in global jihadism and maintains close ties with Syrian al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusrah. Aside from the Islamic State, Ahrar is now the single strongest rebel force in Syria. Turkey’s role in supporting Ahrar illustrates how Turkey has compromised its ambitious policy goals in Syria and raises questions about Ankara’s reported planned intervention in Aleppo to carve out a “safe zone” along its border with Syria.

Turkey changed its approach to the Syrian conflict in late 2011 after concluding that Bashar al-Assad’s hold on power had waned and that his overthrow was imminent. Up until then, Ankara had adopted a cautious approach to the budding insurgency, owing to Turkey’s growing trade relationship with Syria and concerns that the collapse of the Syrian government would empower the most powerful Kurdish political group inside Syria, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), and result in millions of refugees fleeing for Turkey. The PYD is linked to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a U.S. and Turkish-designated terror group that has waged an insurgency against the Turkish state since 1984 with the hope of achieving greater autonomy for Turkish Kurds.

Turkey first sought to pressure Assad to make cosmetic political changes to appease the initial Syrian protest movement, but escalating state violence led Ankara to break relations with Damascus in September 2011. Turkey then began working to hasten Assad’s overthrow through a dual-pronged policy: Politically, Ankara sought to empower the Syrian political opposition-in-exile, and the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood in particular; militarily, Turkey partnered with Qatar — and, to a lesser extent, other Gulf states — to support Syrian rebels. Ahrar became a major beneficiary of Turkish policy, receiving weapons and political support throughout the conflict. Ankara has allowed the group to base inside Turkish territory and to have freedom of movement in the country’s two largest cities, Istanbul and Ankara.

Ahrar has evolved from several dozen men from rural northwest Syria to a country-spanning “movement.” Ahrar’s scope of activities — including military brigades, political offices, and relief operations — makes the group difficult to define neatly. It has English-speaking political officials happy to reach out to the West, as well as more hardline commanders and ideologues who grew up in global jihadism and never really left. An Ahrar fighter might be a true believer, or he might just be a conservative mountain villager who joined because his cousins did. Syrian civilians often describe Ahrar members as religious, but also reluctant to impose themselves on others. The leadership has a reputation for being more politically savvy than other rebels — as a group with which you can engage and negotiate — which may explain Ankara’s support for the group.

Still, Ahrar’s stated political project is defined and exclusive: toppling the Assad regime and establishing an Islamic state in Syria. The group has expressed an openness to broader political participation — a legislature-like body that would implement an Islamic constitution, for example. Yet it has been emphatic that it is unwilling to compromise on its basic principles, including that “democracy” as such is off the table and the (Sunni) Islamic character of the state is non-negotiable.

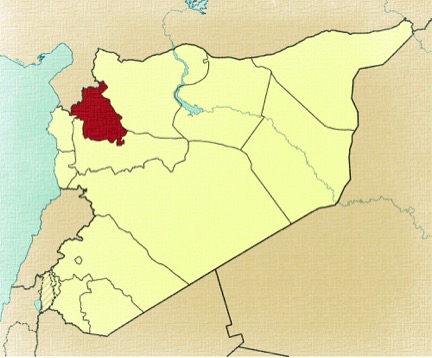

The United States has been reluctant to engage or support the group because of its links with the global jihadist movement, and Nusrah in particular. Ahrar allegedly went as far as to provide Nusrah with material support after the April 2013 establishment of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), when many of Nusrah’s fighters joined with ISIL and took Nusrah’s bases and materiel with them. More recently, it was Ahrar and Nusrah that formed the dual core of Jeish al-Fath (the Army of Conquest), a coalition of northern Islamist and jihadist rebels. With Turkish backing, Jeish al-Fath recently drove the regime’s military from most of its remaining redoubts in northwest Syria’s Idlib governorate, a mountainous, mostly rural province adjacent to Turkey and proximate to the regime’s coastal stronghold.

Thanks in part to Turkey, Idlib is now almost completely free of the Assad regime, making the province a test for northern rebel governance and Turkey’s Syria policy. To be sure, governance in Idlib, as in other rebel-held areas, faces an impossible set of challenges. Chief among them is the regime’s relentless aerial bombing, a constant threat of random death that prevents the resumption of normal life. Some civilian relief workers and municipal employees have nonetheless remained to deliver humanitarian assistance and heroically undertake what would otherwise be banal tasks such as holding town hall meetings, fixing electricity lines, and maintaining water pumps.

Syria’s Idlib governate

But real power in Idlib sits with rebel and jihadist factions, which mostly concern themselves with law and justice: maintaining security and backing two competing systems of Islamic courts with overlapping jurisdictions. Ahrar and other rebels are behind the multilateral Idlib Islamic Commission, while Jabhat al-Nusrah and its ultra-extreme splinter Jund al-Aqsa have backed “Dar al-Qada” (the Judiciary). The Islamic Commission applies Islamic law but avoids some of its more extreme manifestations, including the implementation of hudoud punishments such the amputation of hands. Nusrah’s Dar al-Qada courts, meanwhile, have become notorious for harsh, controversial rulings: for example, executing women in the street for prostitution. But these courts also have real writ to an extent the Islamic Commission courts do not because they have motivated Nusrah and Jund members ready to kill for them.

Ahrar’s members are now the relative moderates in Idlib, in part because more nationalist rebel groups have either been dismantled or put under the jihadists’ thumb. Syrian members of Ahrar are often unhappy to see interlopers imposing an alien version of Islam on their friends and neighbors, and it is Ahrar to whom civilians look to protect them from jihadist excesses.

Yet Ahrar shoulders some of the blame for those same jihadists now running amok. For example, Ahrar reportedly played a key role in inviting jihadist foreign fighters into the Syrian jihad. And the most dramatic excesses typically come not from Ahrar itself, but rather from out-of-control jihadist allies that fight alongside the group. When rebels took the Armenian Christian border town of Kasab — reportedly after Turkey allowed them to use its territory to outflank the Syrian regime — it seems it was Nusrah and other jihadists, not Ahrar, who smashed crosses and desecrated churches. A similar dynamic was on display more recently as Jeish al-Fath, the Ahrar- and Nusrah-led coalition, swept down Idlib province. Jeish al-Fath is backed by Turkey and also includes relative Islamist moderates like Feilaq al-Sham, yet it has also brought with it Jund al-Aqsa, whose members seem to largely be psychopathic ISIL sympathizers.

Ahrar’s reputation for relative moderation requires one to view the group almost exclusively from a Sunni Arab vantage point. In fact, Ahrar has played a key role in feeding sectarian and ethnic polarization in Syria, helping Assad maintain his support among religious and ethnic minorities. Ahrar was one of the first rebel groups to unapologetically cast Syria’s revolution as a sectarian war: Now-deceased Ahrar chief Hassan Abboud used his first Al Jazeera interview in 2013 to frame the war in terms of a region-spanning sectarian conflict against not just a “Shi’a Crescent,” but a “Safavid sickle.”

And it was Ahrar and Nusrah — later Ahrar, Nusrah, and ISIL — that formed a sort of multi-headed jihadist monster fighting in eastern Syria against the PYD’s militia, the Kurdish Peoples’ Protection Units (YPG). It was fear of these Arab jihadists that drove Syria’s Kurdish minority to coalesce around the PYD for political representation and the YPG for protection. Ankara seems to have used Ahrar (and, indirectly, its jihadist allies) as a political and military counterweight to the PYD/YPG, keeping what Turkey views as a grave Kurdish terrorist threat bottled up in a few disconnected cantons. Yet it is now clear that this strategy has only empowered the group Turkey sought to marginalize.

Recently, the Kurds — with Western air support — broke out of these cantons and took what had been considered non-Kurdish or mixed areas across much of Syria’s north. Ankara now wants to ensure that the Kurds don’t push west across the Euphrates into ISIL-held east Aleppo, which would position the YPG to drive on to northwest Aleppo’s Kurdish enclave of Afrin and establish a Kurdish statelet along most of Turkey’s Syrian border.

Ankara has been pushing instead for non-Kurdish rebels — also backed by American airstrikes — to drive ISIL from the area. Turkey has been working assiduously to convince the United States to impose a no-fly zone over Syria, and it had previously refused the United States access to Incirlik Air Base until its demands were met. After nine months of U.S.–Turkey haggling (accelerated by a dramatic ISIL-linked suicide bombing in the Turkish city of Suruc), the two countries reached an agreement to base American strike aircraft in Turkey. Ankara is also reportedly moving forward with its east Aleppo “de facto safe zone,” an area that the implied threat of Turkish force will turn into an effective air-exclusion zone. This area would deny ISIS its last land border with Turkey and allow Syrian refugees to return without fear of bombing — and it would also situate Turkish-allied rebel forces on the western edge of PYD/YPG territory, thus coincidentally preventing the YPG from pushing further west.

There have been conflicting reports about what sort of agreement (if any) the United States and Turkey have reached on this eastern Aleppo safe zone, and what role that agreement allows for Ahrar. Some sources have said the United States and Turkey agreed to exclude both Ahrar and Nusrah from the zone, while others have reported the opposite, that Ahrar will have a role and may in fact be Turkey’s leading rebel partner on the ground. U.S. officials, for their part, have indicated that the makeup of the “hold force” in eastern Aleppo is still being discussed with Turkey.

For now, though, Ahrar appears involved and ready to expand its role in the area. While Nusrah seems to have surrendered its north Aleppo positions along the ISIL line to more moderate rebels, Ahrar has remained in place opposite ISIL in the northern Aleppo countryside. Ahrar is thus positioned to drive east alongside a Turkey-backed offensive. Ahrar has effusively praised both Turkey and the safe zone and is already advertising a new push against ISIL positions in the area.

A prominent role for Ahrar would seem to run counter to American preferences, and it would also raise questions about the Syrian opposition proto-state Ankara is trying to foster along its border. If Ahrar assumes military leadership in eastern Aleppo, does that also mean that Ahrar sets the terms for rebel governance? Before ISIL swept in, after all, Ahrar had deep roots in the area. (Its current commander, Hashem al-Sheikh, hails from the eastern Aleppo town of Maskanah.) Moreover, if Ahrar advances east, will Nusrah really keep its distance indefinitely? Or will it bide its time before following Ahrar?

The United States may be willing to open a discreet dialogue with Ahrar in the coming months, but Ahrar’s aspirations remain, at base, incompatible with American aims. For Turkey, though, Ahrar is still an attractive partner: strong, effective, and politically capable. Ankara has worked closely enough with Ahrar — empowering the group not just as a fighting force, but also as a political actor — that Ankara has assumed a degree of ownership over Ahrar’s overarching political project. As Turkey prepares for a major escalation of its role in Syria, it remains to be seen whether Turkey will rely on its Ahrar partner in eastern Aleppo, and if so, whether Ahrar can keep full-bore jihadists out of Turkey’s new safe zone. Otherwise, Turkey may inadvertently be building an Aleppo that looks a lot like Idlib.

Sam Heller is a Washington-based writer and analyst focused on Syria. Follow him on Twitter: @AbuJamajem.

Aaron Stein is a Nonresident Fellow with the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, a Doctoral Fellow at the Geneva Center for Security Policy, and an Associate Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute in London. Follow him on Twitter: @aaronstein1.